Serena Williams and the Politics of Images

By: Hina Ahmed

Serena Williams’ Vanity Fair shoot uncovers much to be said about the politicisation of the black woman’s body, writes Hina Ahmed.

It goes without saying that Serena Williams is certainly a force to be reckoned with. As a woman, and more specifically as a black woman, Serena has earned many accolades, with over twenty-three grand slam titles, several Olympic gold medals, and has ranked as the number one female tennis player in the world.

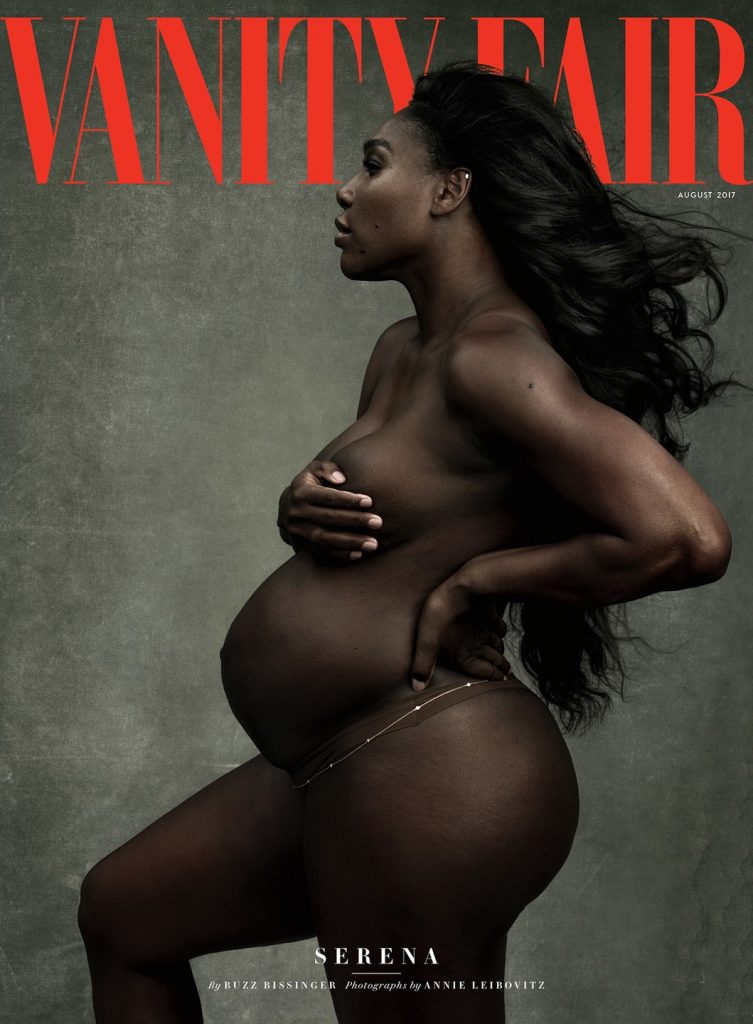

Although she has been predominantly presented as an athlete, Serena now unravels a complex narrative associated with a new kind of image. In August’s issue of Vanity Fair, Serena poses as a nude, pregnant, black woman, occupying space in a different world than the one she’s used to.

On the cover, Serena is standing sideways accentuating her baby bump, covering her breasts with one hand, her long, black hair flowing behind her, and her face peacefully gazing forward. For some viewers, this image embodies a form of resistance to the nefarious nature of racism and patriarchy.

August’s cover of Vanity Fair.

However, a closer look at the narrative behind Serena’s image presents a context that challenges contemporary feminist celebrations of her image as an untarnished manifestation of a post-racial, post-patriarchal, postcolonial world order.

Instead, this image exposes the ongoing proliferation of structures of violence within the context of image representation in the media.

New wave feminists may view Serena’s image as a symbol of victory for black feminism because it seems to signify freedom of expression and self-ownership over not only a woman’s body, but a black woman’s body, as well as that of a pregnant body, seemingly celebrating a nexus of intersections of womanhood, blackness, and motherhood, and thereby enacting a form of racial equity and an explicit exercising of Serena’s right to choose how to use her body.

However, after reading the work of Maria Davidson, author of Black Women, Agency and the New Black Feminism, I realised this conception of the image as a victory is flawed, and instead urge an evaluation of a more contoured terrain that Serena Williams’ image is enmeshed in.

As a naked black woman, Serena’s body carries a different kind of politics than that of a naked white woman. Although the pillars of the patriarchy influence both of these bodies, the exploitation of them is inherently unequal as a result of the black body being situated within the context of slavery.

Davidson’s work in Black Women, Agency, and the New Black Feminism is also significant in contextualising Serena’s image because it evaluates black women’s reproduction in the United States. Davidson argues that after emancipation, black women’s wombs were no longer a productive resource to be exploited, but instead came to be seen as a threat to white society.

When comparing Davidson’s analysis to Serena’s own reproductive body, the question becomes: How does white society perceive Serena’s reproductive image today? Whether or not her image is seen as a ‘threat’ requires an evaluation of the role that Serena’s upper class, celebratory status, and relationship to a white man and father of her child has on how ‘threatening,’ or nonthreatening her image is.

Some feminists may argue that Serena Williams’ image successfully presents a contrast to the denigrated image of the black woman: with her net worth in the millions, her fertility is seen as necessary, and offers a harmless and uplifting image of her race.

I believe this perception of a victory is false because it fails to take into account the oppressive components of class, and the relevancy of class warfare within the context of image consumption. Serena’s wealth and status are the reason this image was produced in the first place, and it is a wealth and status unattainable by many, but especially by other black women, given the structures of patriarchy and white supremacy that still hold so much power.

To provide some context, in 2010 an alarming billboard emerged in Austin, Texas that read, “The Most Dangerous Place for Black People is in the Womb.” In other words, according to this billboard, the black mother is the most dangerous person in society, a woman who cannot be trusted to create and carry a life.

The black woman’s body is therefore a body whose hazardous reproduction needs to be controlled through its utter eradication, the ultimate goal and victory for a eugenic agenda.

So, we must ask: How is Serena’s image interacting with images of the past, like the billboard, that found its footing in the precarious agenda of white supremacy? Is her image seeking to transcend that narrative and create a new one? Can an image ever have the power of historical transcendence – and if so, should it?

This historical tapestry of how images of black people have been read in the past presents a context that means we need to ask how Serena Williams’ image is embedded within it, outside of it, and perhaps somewhere in between it.

Serena’s image has a racialised context that cannot be ignored. To simply suggest that Serena’s image is a ‘win’ for feminism is not only reductionist, but also an active expression of an implicit violence against the black body as a result of historical de-contextualisation.

Through choosing to contextualise both the production and consumption of images, we can shift away from being passive consumers to active ones, thereby facilitating an engaged global consciousness; the quintessential precursor needed toward becoming active agents of social change.

Hina Ahmed is from Binghamton, New York. She holds a BA in History and an MA in Education from Binghamton University. She enjoys writing poetry, short stories, and is in the finishing stages of her novel: The Dance of the Firefly. Hina’s published work has appeared in EastLit Literary Journal, Press and Sun Bulletin, and Pipe Dream.

This is helpful, thank you Hina. But I wonder about this statement. ‘Serena’s wealth and status are the reason this image was produced in the first place.’ Just tracing it back one step, isn’t it that William’s talent gave rise to her wealth and status, which ultimately led to the production of this image?