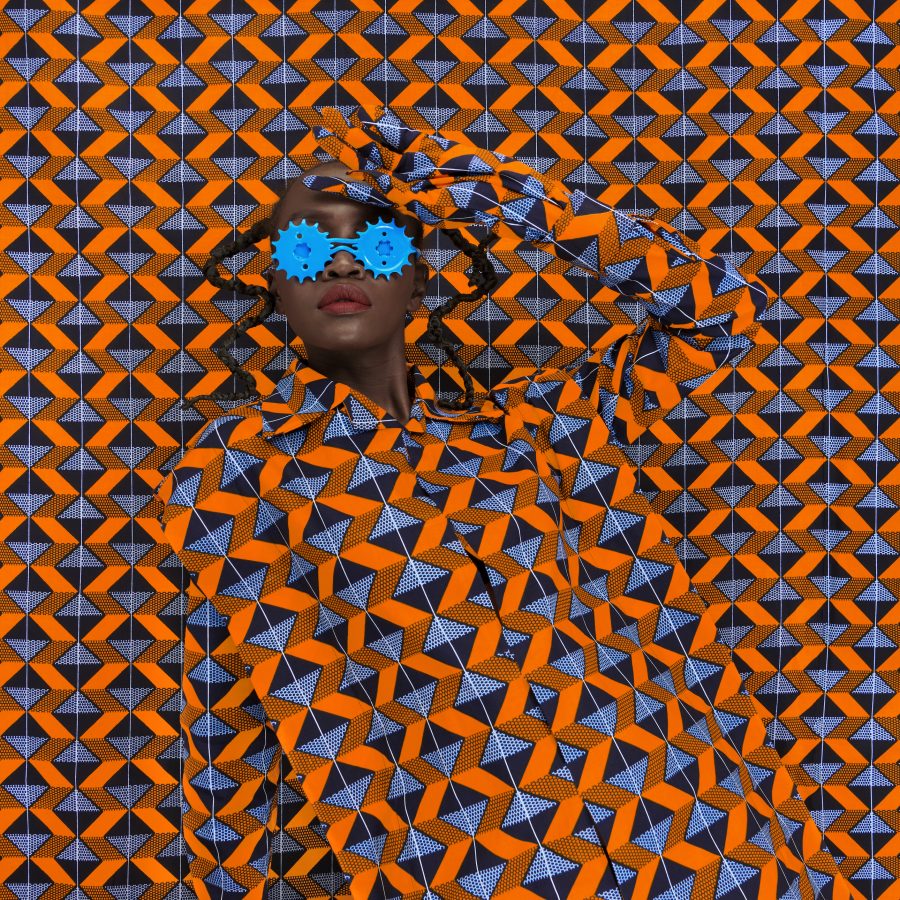

Thandiwe Muriu’s vibrant portraits bring Kenyan culture to the fore

By: Archer Magazine

In her series Camo, photographer Thandiwe Muriu draws on the slick aesthetics of fashion photography to reinterpret contemporary African portraiture. These bright, playful images immerse her models in colourful textures until they simultaneously disappear into the background and burst from the frame. Exploring how individuals lose their identities to culture, Muriu’s work interrogates contemporary self-image and brings aspects of Kenyan tradition to the fore, from reappropriation of everyday objects to traditional architectural hairstyles. Muriu aims to reclaim the self love of the African woman, who is often excluded from beauty standards in her own country.

Featured Image: ‘Camo 34’ by Thandiwe Muriu

Portrait of Thandiwe Muriu, courtesy of Thandiwe Muriu

When did you first fall in love with photography? Have you always been drawn to portraiture?

My journey began at 14 years when my father taught my sisters and I how to use digital cameras. I like to say before then that I had all this art inside of me that was looking for an outlet but hadn’t found one yet. I couldn’t really draw or paint, but right from my first interaction with the camera I knew there was a connection between photography and I.

Every day after school I would rush home and finish my homework so I could photograph clouds, flowers and anything I could get my hands on before the light faded. My father had all these old photography magazines that I would pour over during the weekends. I was hungry to learn anything and everything about photography!

My elder sister used to collect Vogue magazines and over time I developed an interest in wanting to create pictures like the ones I saw on the covers – these magical, flawless images… I convinced both my sisters to model for me, using bed sheets as the background to create all these elaborate shoots. For lighting, I used foil paper as a reflector (I wonder if my mother ever figured out where all her foil paper went!).

After every shoot I would put the pictures up on Facebook and, about a year later, somebody inboxed me and asked me how much I would charge for a photo session. I thought, Wow! You mean I can get paid to do this? And that’s how my career began.

‘Camo 29’ by Thandiwe Muriu

‘Camo 5’ by Thandiwe Muriu

Your work explores how individuals lose their identities to culture. What made you decide to approach this subject and how did you come to do so in the way that you have?

When I first began photographing personal work in 2015, the idea was simply to discover who I was as an artist and fall in love with photography again.

In my images, the colourful prints act as the backdrop that I can celebrate my culture on. In this body of work, I wanted to celebrate everything I had struggled with in my own beauty journey- my hair, my skin and my identity as a modern woman in living in a more traditional culture.

The series is titled Camo because of how the subject of each image camouflages into the background. It’s a commentary on how as individuals, we can lose ourselves to the expectations culture has on us, yet there are such unique and beautiful things about every individual. It’s a little ironic – I want my models to blend into the background even as they stand out.

As the body of work has grown, more and more my subjects are blending seamlessly into the backgrounds. Almost as if to indicate the coming together of my two worlds as a modern woman living in a traditional culture.

‘Camo 33’ by Thandiwe Muriu

The colours and textures within your images are striking, playful, and captivating, as are your chosen models. How do you plan your shoots?

I follow a very systematic process for creating my work. The story of Camo all begins with the fabric. Each textile has its own personality that I want to unveil in my work.

Many times, you will see men, women and children walking along the streets of Nairobi dressed up in outfits made from these brightly coloured traditional fabrics. They wear these fabrics whenever they want to look their best, especially at big events like weddings. The same fabric could be seen on several women, but they will all wear it in very different designs which are a reflection of their personality. It is a beautiful thing to see. I typically use the more modern geometrical prints that my generation wears in bold colour combinations.

The next step is to design outfits that pair well with the print. Working with various local tailors from Nairobi’s many marketplaces, I get the clothing stitched. Depending on the complexity of the pattern, a garment can take up to two weeks to be completed.

While the clothes are being stitched, I design and fabricate the accessories. The objects used in my work are items I interact with daily as a Kenyan. They were used throughout my childhood and my mother and grandmother interacted with them often throughout their own lives. I usually find objects in the local supermarkets and informal marketplaces – places where any Kenyan would frequent.

‘Child’s Play 2’ by Thandiwe Muriu

Objects are an integral part of the daily lives of Kenyans and are often a big component of beauty culture. ‘Camo 29’ uses mosquito coils and ‘Camo 33’ sprockets reminiscent of those found on the popular Kenyan Black Mamba bicycle. I have used bottle tops, plastic combs, sieves, straws, and even bottle cleaning brushes. This is the most enjoyable part of the creative process because it requires me to see ordinary objects as the foundation for exciting fashion accessories.

Traditional hairstyles are an integral part of my work and I research styles historically popular across Africa then design modern interpretations of them for a hairstylist to create. It is a collaborative process because not every style works the way we assume and many times changes must be made when I am taking the actual photographs. For every image the subject’s hair is braided and styled from scratch in a process that takes anywhere from one to two hours.

When all the different elements are finally ready, I bring them together on one subject in one photograph to create the mesmerising Camo series.

‘Camo 27’ by Thandiwe Muriu

Can you tell us a bit about the images recently shown as part of PHOTO 2022 specifically?

The bursting loops of the African print of ‘Camo 34′ brings to mind the humble atom found in the deepest core of every human being. I wanted to celebrate being human – the theme of PHOTO 2022 – and to celebrate the beauty of life in its various forms, whether it is the unseen depths of life, or the actions and emotions which we all carry.

To me, the centre of being human is the ability to feel, to experience, to internalise those experiences and turn them into the core of whomever each one of us – good or bad – becomes as a person. It is the colours of life that remind us that we are human. To quote BBC Earth: “But to be human is to be at the centre of our own universe, to experience life in all its colours and all its potential.”

What’s next for you and your work?

I will continue to explore cultural themes from my heritage as I embrace new ways to creatively express myself.

‘Camo 16’ by Thandiwe Muriu

Thandiwe Muriu is a photographer born and raised in Nairobi, Kenya. She is passionate about celebrating and empowering her fellow women.