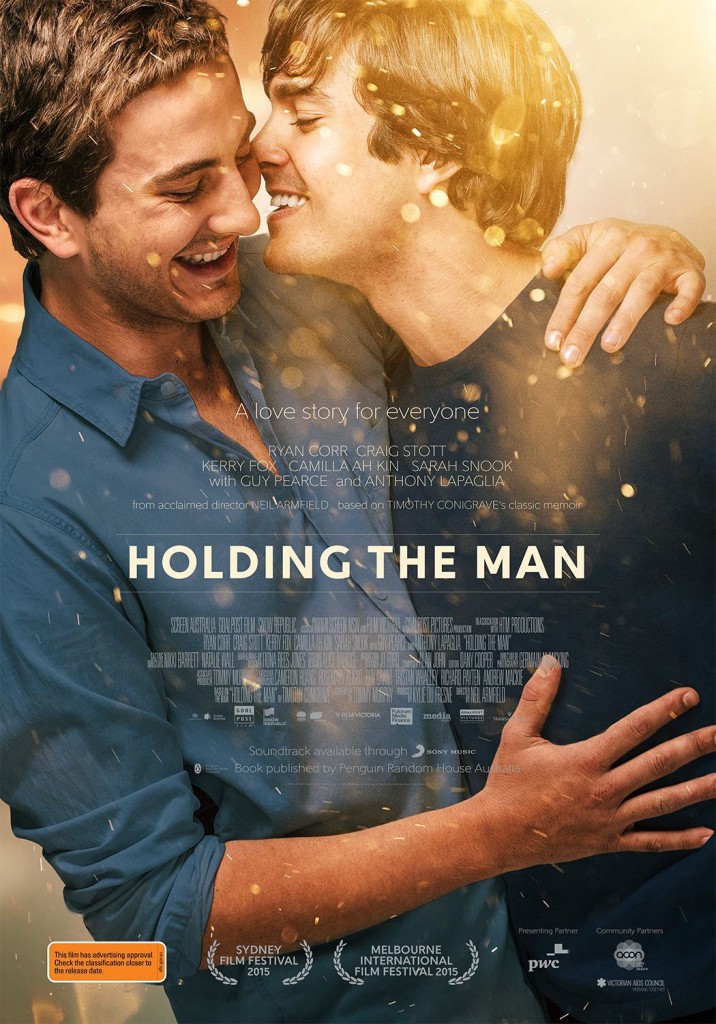

Holding The Man: A love story for everyone

By: Aleczander Gamboa

Whenever we think of AIDS, we are immediately drawn back to the 80s when its emergence was at the forefront of Australian media. To say that it was a difficult period would be a major understatement – people were getting the virus left and right, casual sex received a bad reputation and our government hoped the use of fear tactics in the form of a grim reaper would decrease escalating statistics.

But for the gay community, the 80s were also a time where prejudice and bigotry ran rampant in society, with the virus leaving a path of devastation in its wake as it unjustly took away so many of our close family and friends. However, despite this harrowing period, it was an incredible time for gay men as the world witnessed a unique community sticking together as best they could while they fought off homophobia, intolerance, and the AIDS virus at large.

Because many of these occurrences happened while I was still a baby, anything related to the history of AIDS and its impact on the gay community were largely lost on me. I discovered Timothy Conigrave’s memoir Holding The Man when I was in secondary school, and being a young, shy boy who was extremely insecure about his sexuality, I would only open the novel when no one was around.

Back then, contracting the virus was my biggest fear of identifying as a gay man, and because I didn’t have the mature mindset to handle such a complex issue, I didn’t finish the memoir. Fast forward to 2015, where I picked it up again after learning that it would be turned into a film.

Timothy Conigrave’s Holding The Man was (and still is) regarded as the diamond in the rough during this traumatic AIDS ridden era. Written on his deathbed, Conigrave died only 10 days later and never saw the acclaim the novel received.

The public’s apprehensions of whether or not the film would do the memoir justice was definitely something that hadn’t gone unnoticed by Director Neil Armfield, who was well aware of the enormous pressures in adapting such an iconic gay novel into a film.

“There are huge responsibilities involved in taking on this story. To the power and popularity of the book. To Tim and John themselves, and their many friends alive today. But most of all, to Tim’s and John’s families, still grieving their loss more than twenty years later: how difficult it must be for them to face the idea of their story becoming even more public,” he said.

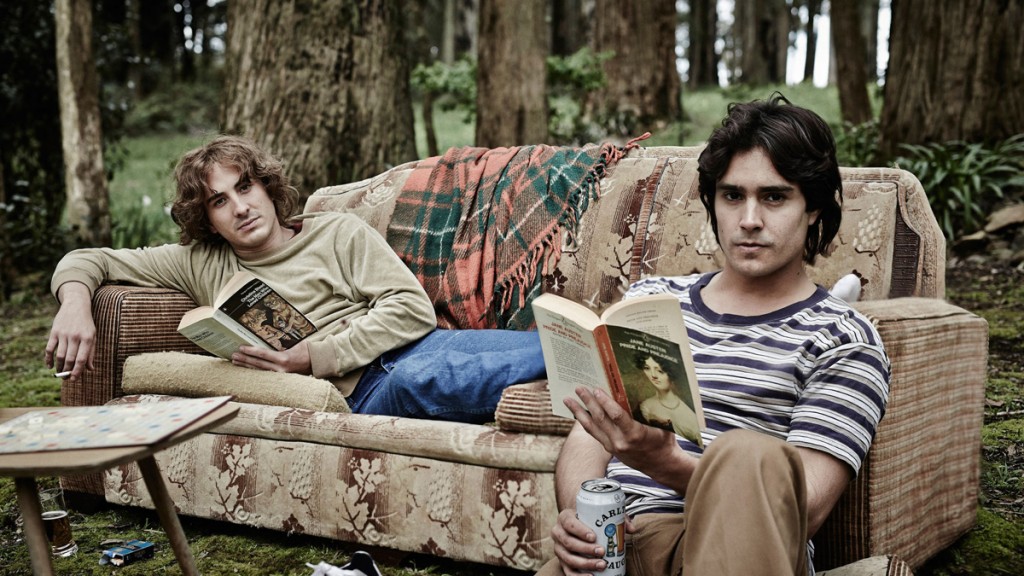

Armfield describes the love between Conigrave and Caleo as “epic in nature” – a story that speaks across different generations both young and old. Filmed through anamorphic lenses, he believes that the visual aspect carries a certain power in impacting audiences in a profound way as they witness the vehement rejection their love received.

“The rejection of Tim by John’s family and, while John is dying, the way that all of the forces gather to deny their relationship, to downplay AIDS and particularly, to regulate Tim to being one of John’s friends at the funeral, these events become a creative spur for Tim,” he said.

“For an audience, having experienced the love – which you’re able to do in such a personal and beautiful way in a film – you feel the injustice of that denial so powerfully. Tim’s memoir and therefore the making of the film becomes a way of making their love eternal.”

Meanwhile, it was the brutal honesty of Conigrave’s voice in the novel that motivated screenwriter Tommy Murphy to turn the novel into a play for the Griffith Company in 2006, and later into the film that we see today.

Timing wise, neither Murphy nor Armfield foresaw that the premiere of the film would be during a time where marriage equality was a heated debate in Australian politics. Call it convenient timing or just plain luck. Nonetheless, Murphy hopes that the film will not only showcase the beauty of love in all of its various forms, but also contribute to breaking down the stigma still attached to AIDS.

“HIV is a different illness now than it was in the 80’s and early 90’s. The AIDS epidemic happened in my city in living memory. We can forget that very easily and I think that the film honours that history and honours the real lives that were lived,” he said.

“To love someone is to fear losing them. The power of this story is that it is a story of time running out and the need to hold to every moment.”

From a critical standpoint, it’s safe to say that the film adaptation does the memoir justice. Like the novel, it leaves little to the imagination, with the film presenting a beautiful balance between intimacy and grief – from passionate sex scenes to the more heartfelt moments like when we hear John’s last breaths of life and see Tim’s tears thereafter, the film manages to combine humour, heartbreak and hope into one neat little package. It’s this visual aspect of film – the fact we see their feelings expressed through their facial expressions and body language as they are exposed to trials and tribulations – that really hits the audience.

Although the film showcases a significant period in Australian history it also serves as a reminder of how far we have come in terms of AIDS research and acceptance of the gay community. Whether as an adult watching the film for nostalgia or as a young person looking to see what all the fuss is about, Timothy Conigrave’s Holding The Man demonstrates how humans, gay and straight, have the privilege of experiencing love and all the feelings that come with it.

Hence the tag line: A love story for everyone.

Holding the Man is in cinemas now.

Aleczander Gamboa is a freelance writer and editor. He is currently the sub-editor for Blaire Magazine. He regularly blogs at Thoughts With Dreams and tweets under @aleczZzander.

Griffith Company … Griffin Theatre Company***