Fa’afafine: All Hail the Queen (Samoan Sashay)

By: Amao Leota Lu

Western constructions of gender and sexuality can be restrictive for individuals who are Fa’afafine, whose identity goes beyond the binary.

Amao Leota Lu, as told to Bobuq Sayed, former Archer Magazine co-editor and deputy online editor.

Anxiety levels for trans and gender-diverse people are high. It used to be about sexuality stuff, but people still don’t have their heads around what it means to be trans or non-binary. Then again, the public isn’t paying my bills or getting me housing, so I stopped worrying about what they think.

And back when I was at school, I used to wish I was white. It took me a while to own my colour. Today, people of colour (POC) take ownership of our identities.

There’s still a lot more work to be done – for people with disabilities and intersex people, for instance – but things are better. We’re not necessarily in big organisations, and that is why visibility and stories being told from our own perspectives are so important.

I wasn’t initially sure about the label ‘queer elder’, but now I love it. Young people call me ‘aunty’ and I say with humour, “Yeah, but I look younger than you.” I tell them I prefer to be called ‘younger cousin’ because I’m better-looking than they are, and we laugh.

Sometimes I’m so off-put by some of the older LGBT lot because they’re so stuffy, and I think, How are you going to be warm and welcoming so that younger people open up when you’re gatekeeping? There’s such a big intergenerational gap here, and I think that’s a big problem.

When I’m with my POC, though, the barriers aren’t there. Especially younger queer and trans people of colour (QTPOC) – y’all are my babies, hello. I’ve been there; why would I want to make it any harder for your generation when I’ve been there? Young QTPOC respect their elders, and I’m encouraged and inspired by them. They’re so political, opinionated and a lot more outspoken, and I love that.

We weren’t able to be political back then; we were whitewashed, we were colonised and we didn’t know any better. The younger generation understands that queerness is about more than sex – there’s climate justice for sea levels rising on the islands, or the reality that trans women of colour are being killed at an extreme rate. The next generation is going to look even more different.

I migrated from New Zealand to Australia around 1982, when I was about 12.

When I was growing up, Australia was so white-dominated. My school was mostly Europeans – there were Greeks and Italians – and some Lebanese. Evolving into who I am today involved lots of challenges. I struggled with my identity because I came from a place where there was a big Polynesian community.

Everything seemed different here. The pace was a lot faster. I never realised what designer labels were. I was hanging out in my black slip-on karate shoes, which I still love and which were two or three dollars from the markets.

My family is from the Pacific island of Samoa. Where I come from, people don’t have a lot, but they make it work for themselves. Kids are so judgemental, and trying to figure out where I fit in took a while. I battled the fact that I was a bit different for so long.

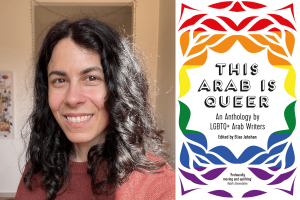

Image: Jade Florence

Church for Islander people back in the day – and even today – was like a community centre. They saw it as a healing space. There were no Pacific Islander support groups, so we had to make do.

My family life was centred on church, and that I struggled with. It was almost like a yo-yo effect: I went to school and lived in one world for a moment, then came home and had to switch gears completely. It was about assimilation: trying to find a middle road where I could feel accepted and be happy.

That was a challenge for me. The God and church stuff was especially hard because it was hammered into me – the coloniser’s religion. You had to adhere to Samoan responsibilities to do with being from a good churchgoing family, and then navigate the other, Western social rules, which are so different.

Once upon a time, she wanted to be Kylie Minogue, but then there was Janet Jackson.

I found good company in two goth Pacific Islander cisgender girls, and they never made a big deal about my mannerisms. They never questioned anything; they just accepted me.

We would get stuck into their parents’ alcohol. These two girls in military gear and black Doc Martens boots loved R&B and hip-hop music, and they were just out there as outsiders. Without them, I would’ve felt lost and lonely, with few or no friends to hang out with.

Everyone else was still making jokes about gays and stuff, but I never struggled with school itself because I was a good student. I had good friends, and it helped that my classmates were afraid of my cousins in the area.

While I never was open about it, I had also struggled with sexual abuse. That was a big part of my being unable to find myself and not feeling good about myself. That’s already hard to do when you’re young, but it’s even harder when you’re trying to process abuse alone. It’s overwhelming, and it created big periods of my life where I was totally lost.

Once I left school, personal relationships were tough – until I evolved to become Amao. I left home and got involved with someone 20 years my senior, who physically abused me a lot. Because I was so in love with him, we eloped, and for a while it didn’t matter. I didn’t realise that I was receiving some of the same abuse I had encountered as a child.

It took me so long to clock on to the fact that the love I’d made up in my head was not the love I was receiving. I so desperately yearned to be loved. In those days, we didn’t have community-health organisations to help with counselling and pathways. After going through physical abuse, I just wanted acceptance and to be loved– and I had to make sense of that all on my own.

That’s when I first got introduced to nightclubbing and the gay scene in Sydney. We would go to local clubs and to Kings Cross to feel at home. It had a real openness; your eyes were open to everything. It was a real educational experience – you had strippers, drag shows and people brawling outside – and that was my reality.

But it was also very white. I guess, for me, it was a catch 22. It was good to party among a community, but there weren’t any people of my culture or colour, with similarities to who I was.

During the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, there was an ad that was playing on all of the TVs – a bowling ad with the grim reaper in it, basically scaring people into abstinence – and it was a heavy thing to go through as a community. For many of us, there was already no being open about gender or sexuality. We became even more secretive because we were afraid of being attacked; that scare factor was huge.

All this stuff made finding the parts of myself that were real even harder.

Fa’afafine is a layered term, and it’s non-binary. In Samoa, it was seen as a third gender and, to a certain extent, it still is. We also have a new term, Fa’afatama, which is for trans-masculine people.

Binaries are such a colonial way of thinking, and – unlike in Samoa, where there are no medical means for you to change your gender – the West puts so much pressure on trans people to affirm their gender in certain ways. I decided to go on hormones here as a personal choice.

There was also the fear of being judged within the trans community I knew: it was either you were on hormones or you weren’t. If not, you were not considered trans. So there definitely was the added pressure of assimilating within Western trans beauty standards.

Being away from Samoa meant it took longer to own my Fa’afafine identity. One of the beautiful things about Samoan culture is that, within it, I’ve never had to explain where my gender sits in society. And my family supported me either way because the way a Fa’afafine expresses their identity depends on the individual – you can still be feminine and dress the way you want. I never had a coming out; I just evolved to become Amao.

Image: Jade Florence

That happened after a good friend passed away in New Zealand. Something changed. I woke up and I thought to myself, What would make you happy? At that time, I was still living as a boy. I told myself: You have this other person living within you, you are happiest when you are them, and you’re angry when you’re not them. It was a touch-and-go situation, but I decided to make a break for it and embrace my identity.

In American Samoa, they have a different medical system: trans girls can travel to Hawaii or the mainland US and get procedures done or go on hormones. But you can’t just get on a plane and travel anywhere you want if you’re from mainland Samoa, like me. It’s only when we move to places like the US – because we’re competing with every other trans person – that some Fa’afafine individuals succumb to the medical pathway.

Growing up in New Zealand and Australia, I remember older trans people telling me that you’re either a gay boy or a trans girl; there’s no in-between. That’s what I was brought up with here: non-binary was frowned upon.

People still have a long way to go in educating themselves, especially outside of LGBTQIA+ communities. If I was in Samoa, it probably wouldn’t have happened.

I scored a job through an employment agency working in high schools in Sydney. They couldn’t see me when they interviewed me via teleconference, and I think that’s how I got the job. The main woman interviewing me knew about my gender identity, but she let it fly.

I did a 360 into full femme, and that worked out for me. I would go down the Hume Highway for work and people would toot their horns. That was so liberating for me – you put your high heels on, your blouse, your skirt, you do your hair and make-up, and you just do it.

I would sashay to work, and getting toots from the middle of the motorway made me realise I must be doing something right. I didn’t give a shit. There were housing blocks full of Lebanese immigrants who’d look out at me and I’d sashay for them, doing my Janet Jackson nasty.

When I look back on it, I don’t know how I did it – but I was getting money, had stable housing and could afford medical stuff. Those three things made such a difference for me; not many trans women of colour have that.

Years later, though, when I was unemployed again, things started looking different. Suddenly, my gender status became a problem for employers, and opportunities were much more limited. That’s when I came into sex work. It was never something I thought I’d get into, but I just had to do what I had to do to survive.

That was a real eye-opener for me. A housemate I lived with had taken me to the Cross and had taught me the ropes. I quickly learned to be strong and very focused, and how to hustle. You’re being judged for the way you look and, sexually, you’re made vulnerable.

The money was good, but some of the mental challenges and the people you met on the street, or even privately, were challenging. There was such little support for us, and it was so rare for working girls to seek help. You became your own counsellor, and you had to learn very quickly how to juggle that.

There were a lot of positives – the luxuries of men and money – but there were negatives, too, like guys who insisted on sex without condoms or would come in while on drugs. But options were limited. I wasn’t entitled to Centrelink and got tired of job rejections.

Could I have done this journey any other way? No. I’m so proud to be Fa’afafine. It levels me out, especially because I’ve fought so hard for it.

In my own culture, I’m so embraced. There is a place for me historically, and it’s still there. My parents migrated to make life better for us, but sometimes I wish I had grown up in Samoa because I wouldn’t have struggled so much with some of the mental challenges I’ve faced.

But it is what it is. I’m so grateful for my support networks, which I’ve had to fight for. As a Fa’afafine person, you have to push a lot harder. Looking at the whole picture, and seeing where and how my experiences fit with those of other trans and gender-diverse people across the world, it’s humbling. Our struggles are real.

We need to let people know that it’s okay to be brown and trans. We don’t have statistics about trans women of colour murders like they do in the US, but it’s happened here, too. In 2014, an Indonesian trans woman, Mayang Prasetyo, was murdered in Brisbane; she was a friend of mine. Her partner not only beat her up and killed her, but he chopped her up and boiled her body parts on the stove.

It’s a frenzy when it’s a white person who’s murdered, but, when it’s a brown or black person, no-one seems to care. The situation becomes even more extreme when you’re trans. The media found photos of Mayang on her Facebook and ostracised her as a ‘monster’ because she was trans.

It was so devastating for me. I had thought about visiting her and, about a week later, I learned that she was brutally murdered.

When I think of my own Fa’afafine community back in Samoa, I feel a real sense of community. We laugh at everything – we’re not laughing at you, we’re laughing with you. I get so inspired by my Fa’afafine sisters who are kicking up a fuss on a global scale.

I remember watching some of them at a conference in Hong Kong a few months ago, speaking up to leaders of the United Nations about taking our data. We should be able to control that; people have been telling our stories for too long.

The engagement in advocacy work keeps me going. If people like them didn’t exist, I would still be that naive 15-year-old with no idea of who I was and where I come from – and I would fail to exist and would continue to remain in silence.

Resilience comes from bad life experiences; that’s how you grow. It’s a matter of survival. As someone who was sexually and physically abused, did sex work and wasn’t entitled to anything, I needed to push to survive. And I never really complained, because I knew there were people out there for me.

As self-reflection, I say: Haters don’t pay your bills, so you don’t need to worry about them. And still, we rise!

A proud Samoan Fa’afafine / trans woman of colour, Amao Leota Lu is a public speaker, performer and advocate who has worked in the fields of education, the arts, employment, health and community services both in Australia and overseas. Her talks and performances centre on identity, Pacific culture, self-expression, gender and intersectionality.

This article originally appeared in Archer Magazine #11, the ‘GAZE’ issue. BUY ARCHER MAGAZINE