HIDDEN Photography Project: Bringing LGBTIQ domestic and family violence out of the closet

By: Sabine Brix

Trigger warning: this article contains descriptions of physical, sexual and emotional abuse, as well as family violence.

The HIDDEN Photography Project is a stirring conceptual photography project that aims to raise awareness of domestic and family violence within the LGBTIQ community.

The idea was spawned in 2014 when photographer Maya Sugiharto and her co-producer and partner Aviva Minc noticed that mainstream media wasn’t addressing domestic and family violence within the LGBTIQ community.

“There has been a huge amount of imagery and campaigns over recent years depicting heterosexual relationships where the man is the abuser,” Sugiharto says.

“However, there was no representation of this happening within my own community, and I began to question why.”

“We knew that domestic and family violence existed within the LGBTIQ community, but it wasn’t until we had conversations with other people – and as the project progressed – that we learned that people both within and outside of the community had no idea it was happening.”

Aviva Minc, HIDDEN’s co-producer, has experienced first-hand the debilitating effects of violence and abuse and wanted to use her experience to push the issue into the spotlight.

“As a lesbian within the LGBTIQ community, and someone who has experienced manipulative emotional abuse, I felt it would be really powerful to be able to speak the stories of many through a photography project such as this.”

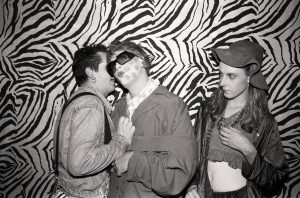

It was Minc and Sugiharto’s passion to expose the issue which ultimately drove the project – a series of poignant photographs of participants re-enacting situations that are perceived to emanate real-life scenarios of violence in LGBTIQ relationships.

These depictions aim to capture the breadth of emotions and situations experienced by both aggressors and victims in a same sex couple.

“You can see in both the gay and lesbian relationships in my photographs that violence in a relationship is not so cut and dry,” Sugiharto says. “There is love and intimacy, yet at the same time so much anger and fear between two men and two women.”

With such a sensitive subject matter, the producers made sure that precautionary measures were taken before the shoot to ensure participants understood the concept the photographer hoped to create. Support networks were also discussed in case emotions were triggered.

The concepts and scenarios staged in the photos were inspired by conversations with the participants in the project, of stories they had heard, or things they themselves had experienced, and research conducted by Sugiharto and Minc. Not all participants had necessarily experienced domestic and family violence themselves.

A common theme that arose was the perceived difficulty victims faced in identifying that the behavior they were experiencing was actually abuse.

Sugiharto says:

“Through talking with our participants, we learnt that often, you question yourself for so long, thinking that it’s you and what is happening is ‘normal’. This is most likely because there is no way of identifying with anything that looks like ‘us’ that we see on television or the big screen.”

Artist Carly-Anne Kenneally was a HIDDEN participant and played the role of an aggressor during the shoot. She explains how the experience allowed her to re-interpret the way she thinks about domestic and family violence in LGBTIQ relationships.

“HIDDEN opened my eyes as to how we define domestic violence and the way in which manipulation and power can be just as damaging as physical abuse,” Kenneally says. “By visually raising awareness of domestic violence in the queer community, I hope that the person affected in the situation realises they’re not alone.”

“I do believe the aggressor doesn’t always comprehend the impact they are having on the other person. The real change will occur if they see these photos or hear a conversation concerning this issue and decide to alter their behaviour.”

Tthe project has been successful for Sugiharto and Minc; exhibiting at Counihan Gallery in Brunswick as part of the Moreland Summer Show and garnering support throughout the wider LGBTIQ community. Importantly, it’s starting conversations for those who need it most.

“We’ve had people on social media – a lot of men in gay relationships – speak out about their own personal experiences,” Sugiharto offers. “We’ve also been approached by some domestic violence organisations who have loved the HIDDEN Photography Project and subsequently begun discussions about other projects on the topic.”

Sheena Boys was also a project participant and recognises how significant the work is in drawing attention to the various complexities and nuances that domestic and family violence can take.

“There are so many levels of violence and, from experience, sometimes it takes time to realise you are in an unhealthy situation,” Boys says.

“HIDDEN Photography Project will hopefully ignite questions within those who view the photography and read the dialogue. Talking to someone is the first step to getting help and raising awareness is key to making change.”

Some of the images in HIDDEN may trigger emotional responses from viewers. To view the work, click here.

If you, or someone you know, is being affected by domestic and family violence contact the National Sexual Assault Domestic Family Violence Counselling Service on (1800 RESPECT) or QLIFE on 1800 184 527.

Sabine Brix is Archer’s online content producer and a freelance writer/composer. Her music features on forthcoming episodes of the award-winning LGBTI web series Starting From…Now! Follow her on Twitter: @sabinebrix