LGBT history: An ode to gay rights activists

By: Matthew Wade

To a group of people I’ve never met,

Although we don’t know each other, sometimes I feel closer to you than I do my own family. When I’m walking hand-in-hand with a boy down the warmly-lit streets of the city, and I pause to lean in for a kiss. When I’m watching a popular, mainstream film about two cowboys falling irrevocably in love with each other.

Even when Mariah Carey’s Heartbreaker plays over department store speakers and I indulge in my desire to channel myself at a karaoke bar. I think of you during these moments because you helped to shape them, and, for that, I’m forever in your debt. Time may have hindered our chance to meet, but your far-reaching and essential work allows me freedom, even to this day.

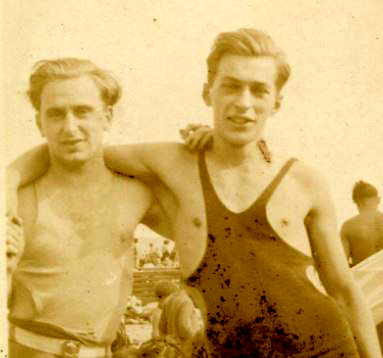

Image: www.homohistory.com

You, the countless impassioned activists who fought for gay rights over the decades, have allowed me to live comfortably and proudly as a young, queer man, and I am more thankful than I can say.

If the gay rights movement was illustrated in a camp and colourful comic strip, one panel might show Alfred Kinsey, who helped to de-pathologise homosexuality in the reports he published about male sexuality in 1948. Another might champion German writer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, who published books about same-sex love in the 1860s.

But when I think of the more recent movement, a meaningful moment is easy to pin-point. It came in the guise of a protest, long before I was born; when Marvin Gaye and Elvis Presley were still crooning on the air-waves. It was an American-based protest, but one that united a previously disparate, global community.

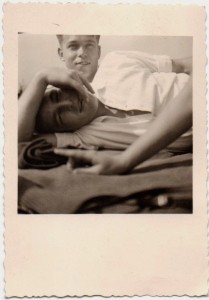

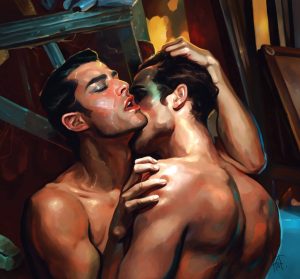

Image: www.homohistory.com

Back then, the police frequently raided gay bars to evict patrons. But on 28 June 1969, a shift occurred. When a group of police officers raided the Stonewall Inn in New York, the clientele fought back. Word spread of the retaliation and a crowd 1000-strong amassed at the bar. The riots lasted three days, and kick-started the gay liberation movement.

Ever since, it has been the uncompromising, tireless efforts of LGBTI activists – such as yourselves – that have transformed the social fabric of the western world, and readjusted its perception of sex, gender and sexuality.

In Australia, the lobbying and consciousness-raising efforts of activists are to thank for many law reforms. South Australia was the first state to begin to decriminalise homosexuality in 1972. Victoria and New South Wales followed suit in 1980 and 1984 respectively. Because of this, my only fear during an evening between the sheets with another boy is how the neighbours will handle my affinity for Boyz II Men.

In 1994, the year that John Travolta did the twist with Uma Thurman and denim was heavily in vogue, the Victorian police raided Melbourne’s Commerce Club during a gay night called Tasty. They publicly strip-searched all 463 patrons and staff, trying to uncover drugs.

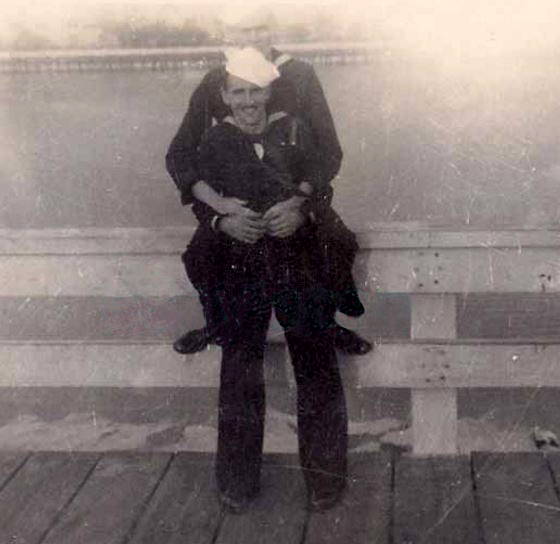

Image: www.homohistory.com

Your response to this was one of outrage. A class action against the Victorian police resulted in the awarding of monetary dam-ages to the many that were affected that night. Earlier this year, on the 20th anniversary of the raid, the police publicly apologised to the LGBTI community, a moment that was truly emblematic of the fruits of your labour. While I watched re-runs of The Bodyguard, you were helping to establish an environment in which my non-normative sexuality had a rightful place.

On streets brought to life by impassioned rallies, you chanted, “Out of the closets and into the streets!” And, although I wasn’t there to hear it, these words have guided me from the moment I became aware of my same-sex attraction.

Growing up in a country town in regional Victoria, I felt comfortable to awkwardly blurt out “I’m gay!” to my parents as a teenager, no longer relying on the stereotypical clichés I’d exhibited for several years prior (yes, Charmed was my favourite television show and yes, my adoration for garishly coloured bow-ties knew no bounds).

During high school, thanks to you I had space to explore my sexual identity, outside of porn and the juvenile sexual banter between classmates. I interacted with like-minded individuals on chat sites created to connect queer youth. I consumed television, film and music with gay subtext, however subtle. I cried harder than I ever thought possible reading Timothy Conigrave’s Holding the Man.

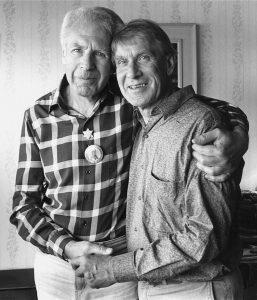

Image: www.homohistory.com

These insights into queer culture profoundly affected me. They helped me to develop my assured sense of identity, and I have your outspokenness to thank for my exposure to them.

In 2013, I was 21 years old, and a film called Blue is the Warmest Colour won the coveted Palme d’Or at Cannes Film Festival. A year earlier, Frank Ocean, a singer immersed in the hyper-masculine world of hip-hop, was comfortable enough to express his attraction to men. You assuaged the fear of stigmatisation experienced by so many. There’s now a boundless, supportive network of queer co-munities around the world, held together by your advocacy for inclusivity.

When the HIV/AIDS virus was discovered in the early 1980s, it was stigmatised by many as a “gay disease”. Homosexual men were further marginalised as a result. The initial mainstream media coverage of the epidemic blamed gay men for their ‘deviant’ behaviour. The Grim Reaper was used to symbolise the health threat homosexual men seemingly posed to heterosexual, nuclear families in Australia.

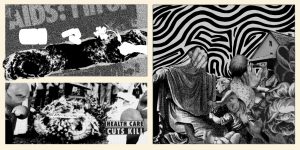

Image: www.homohistory.com

Those affected by the disease – an entire community ripped apart; mourning brothers, friends, lovers – found solace in a newly strengthened, unified community among queer people. The gay press passed on information, the community taught safe sex practices, and hope was found at hundreds of candlelight vigils held in memory of lives lost.

To date, about 36 million individuals have died from HIV/AIDS-related causes. You, and the international community you fostered, work tirelessly to end HIV, reduce stigma and enlighten people while science searches for a cure.

Through this darkness, I’m inspired to contribute to cultural events that celebrate our wonderful LGBTI community. Whether I’m indulging my inner-film geek at the Melbourne Queer Film Festival, or watching a drag performance at Midsumma, my heart is warmed by a common bond between myself and the strangers around me. It’s a comfort I will never take for granted.

Image: www.homohistory.com

Amid all this gratefulness, I’m aware that there are communities around the world who live in environments in which their sexual or gender identities are actively rejected. In Africa, 37 countries still legislate against homosexuality. Universally, sexually and gen-derdiverse youth are four times more likely to attempt suicide than their heterosexual peers. Many experience intersectional discrimination, not only based on their sexual identities, but also on their gender or race.

The movement is ongoing, and now must be undertaken by my generation. Marching in rallies and attending events, I try to channel the relentless passion and courage you showed before I was born.

When I’m in my golden years, and still listening to Earth, Wind & Fire, I look forward to seeing younger queer communities speak out and demand equality in society, helping those of our global family who live in areas still permeated with homophobia and discrimination.

When I realised that I was gay at the age of 12, and felt more alone than I ever have before or since, you lit the fire that has burned within me ever since – you validated my identity, ignited my passion for social change, and encouraged my undying care for the LGBTI community.

To thank you, the best I can do is carry on your era-defining work, and contribute to the impact you’ve already had on the world, all the while singing loudly and unabashedly to Don’t Leave Me This Way.

I love you,

Matt.

This article was first published in Archer Magazine issue #3. Subscribe here.

Matthew Wade is a journalist for the Star Observer and a reporter for JOY 94.9. When he isn’t covering the latest LGBTI news he listens to hip-hop and gets caught in his feelings. Follow him on Twitter: @MatthewRWade

No mention of the 78ers who were brutalised by the cops or the murder of Professor Duncan by the South Australia Police at a beat which spurred on the decriminalisation of homosexuality in SA. The author has failed to mention any of the current issues around state violence Queers in marginalised intersecting communities still face regularly. It’s not all hunky dory now, it won’t be for a long time.