Lesbian feminist in 1990s Melbourne: An interview with my mum

By: Molly Mckew

I always knew my mum was gay. When I was around 12 years old, I would run around the playground boasting to my schoolmates.

“My mum’s a lesbian!” I would shout.

My thinking was that it made me more interesting. Or maybe my mum had drilled it into me that being a lesbian should be a source of pride, and I took that very literally.

20 years later, I found myself doing a PhD on the cultural history of Melbourne’s inner urban countercultures during the 1960s and 1970s. I was interviewing people who had lived in Carlton and Fitzroy in these decades, as I was interested in learning more about the progressive urban culture that I grew up in.

During this time, people in these spaces pursued a freer, more libertarian way of life. They were consistently exploring their sexuality, creativity, activism and intellectualism.

These communities were particularly significant for women living in share-houses or with friends; it was becoming common and accepted for women to live independently of the family or marital home.

Image: Molly Mckew’s mother, taken by the author

In 1990, after divorcing my dad, my mum moved to Brunswick aged 30. Here, she encountered feminist politics and lesbian activism. She began to grow into her creativity and intellectualism after spending most of her 20s being a married mother.

Inspired by my PhD interviews, I decided to ask her all about it. I hoped to reconcile her recollections with my own memories of this time. I also wanted to get a fuller picture of where feminism and activism was at in 1990s Melbourne; a neglected decade in histories of gay and lesbian activism.

During this time, Brunswick was an increasingly trendy suburb that was close enough to my mum’s outer suburbs university without being a suburban hellscape. We lived in a poky terrace house on Albert Street, close to a milk bar where I spent my weekly 10c pocket money on two delicious Strawberries & Cream lollies.

Nearby Sydney Road was dotted with Greek and Turkish cafes, where my mum would occasionally buy us hot drinks and sweets. We mostly ate incredibly bland food from nearby health food shops – there’s nothing quite like being gaslit by carob on Easter Sunday.

As someone who suffers from FOMO (fear of missing out), I was curious about whether my mum found it lonely moving to a new place where she knew nobody. My mum laughs out loud.

“I was not at all lonely!” she says. “It was the eve of a revolution! Women wanted to gather and share their stories of oppression from men and the patriarchy.”

And she was glad to not be around men. “I did not engage with any men for years.”

The epicentre of her activist world was La Trobe University. There was a dedicated Women’s Officer, as well as a Women’s Room in the Student Union, where my mum spent a lot of her time planning demonstrations and sharing stories.

She glows about the activist scene at La Trobe. “It felt like a revolution was about to happen and we had to change our lives and be part of it. Women were coming out and marriages were being broken.”

The women she met were sharing experiences they’d never had the chance to air before. “The women’s studies course I was doing was more like an emotional, conscious-raising group,” she says.

My mum remembers the Black Cat cafe in Fitzroy fondly, a still-operating cafe that opened in 1981. It was one of the first on Brunswick Street; it was “where everyone went”. She also frequented Friends of the Earth in Collingwood, where many rallies were organised.

There was a lesbian open house in Fitzroy and a lesbian mother’s group in Northcote. The mother’s group provided a space to talk about things like coming out to your children, partners coming to school events and “the real-life consequences of being gay in a society that did not protect gay people”.

What was the aim of feminist activism back then? My mum tells me it was much the same as now – a baseline fight for equality.

“We wanted lots of practical change. We talked a lot about equal pay, childcare, and general societal equality; like women being allowed in bars and being equal to men in all respects.”

The “personal is political” was the message and “women took this really seriously”.

It sounds familiar, aside from not being allowed in bars (thank god). I ask her what feminist culture was like back then – assuming it was probably very different to the pop-culture driven, referential and irony-addled feminism of 2022.

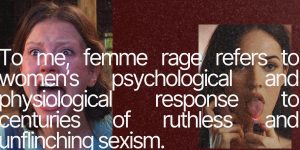

My mum remembers feminist culture as “loud, out, defiant and on the street”. At one of the Take Back the Night rallies, a night-time march aiming to draw attention to women’s public safety (or lack of), mum recalls this fury.

“I yelled at some Christians watching the march that Christ was the biggest prick of all. I was angry at the patriarchy and [that] the church was all about men and their power.”

My mum was in the lesbian scene, which she encountered through university, Friends of the Earth and the Shrew – Melbourne’s first feminist bookstore.

I remember her having a few very kind girlfriends. One let me watch Video Hits every time I went over and fed me dizzyingly sugary food. As a kid, I attended lesbian rallies and helped to run stalls selling tapes of Mum’s own love songs and activist anthems.

“Lesbians were seen as deficient and odd and not to be trusted,” she says about societal attitudes at the time.

“Lesbian women were not really visible in society because you could get sacked for being gay at the time.”

The author Molly Mckew as a child at her mother’s market stall. Photographer unknown, circa 1991

A lot of activism at the time was about destigmatising lesbianism by increasing its visibility and normalcy – which I suppose I also was trying to do by telling all my schoolmates.

“The older lesbians experienced shame and sometimes violence in their relationships – many of them had secret relationships,” Mum tells me.

I ask whether she ever experienced stigma or discrimination, or whether her progressive milieu provided her with emotional shelter.

“I was out most of the time, although not always feeling comfortable,” she answers. Discrimination still happened.

“I was once pulled over by a police officer because I had a lesbian mothers symbol on my car. There was no reason and I got a warning, even though I wasn’t speeding at all!”

Like all activist scenes, or any scene at all, there was division. There was tension between “newly coming out lesbians, ‘baby dykes’ and women who had been part of the gay culture for a long time”.

Separatism was talked about a lot back then. Sometimes if a lesbian or feminist had a son, or didn’t live in a female-only household, it caused division.

There were also class tensions within the scene, which, although diverse, was still dominated by middle-class white women. My mum identifies these tensions as the beginnings of attempts at intersectionality – something that characterises present-day feminist discourse.

“People started to critique the movement for being exclusionary or classist. As I began to perform my own songs at festivals and events, a few women confronted me [about being] a middle-class feminist because I owned a house and had a car. It was discussed behind my back that I had gotten money from my previous relationship with a man. So was I a real feminist?”

But my mum’s overwhelming recollections are of a burning collective energy. She tells me that her songs were expressions of the values in those circles; justice, openness and inclusion. “It was everyone together, shouting for change”.

When I was about eight, we moved away from Brunswick and to a house in Melbourne’s outer east. My mum mostly removed herself from the radical milieu she’d been in and became more spirituality focused.

We still went to women’s witch groups occasionally. I recall the sharp smell of smoke when the group leader’s long black hair caught fire in the middle of a forest ritual. “Sorry to traumatise you!” my mum laughs.

We walk to a nearby cafe and buy lunch. The comfort of Mum’s presence breaks me and I begin to weep about a recent breakup with a guy. But her reminder of how independence is a hard-won freedom and privilege picks me up again.

I’m reminded that while we cultivate our strength, independence and many facets, there are communities that always will hold us.

Molly Mckew is a writer and musician from Melbourne, who in 2019 completed a PhD on the countercultures of the 1960s and 1970s in urban Melbourne. She’s been published in the Conversation and Overland and also co-authored a chapter in the collection Urban Australia and Post-Punk: Exploring Dogs in Space, edited by David Nichols and Sophie Perillo. You can follow her on Instagram here.

Nice article. Just wondering why ‘Mum’ does not have a name or is she just Molly Mckew’s mum.