Police brutality and bigotry as a young Aboriginal person: I am not the problem

By: Jax Sansbury

Content warning: This article discusses police brutality, violence, racism, criminalisation of Aboriginal people, and police aggression towards Aboriginal children.

I’m Jax. I’m 18 years old and I have had more interactions with the police than anyone my age should have.

I am here to tell you that I am not the problem.

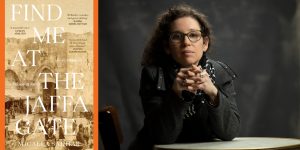

All images by: Claudia Fischer

I am like a flower. I have so many petals that make me who I am, but at the centre of all those petals is my pistil – my Aboriginality. This shapes so much of who I am as a person. My flower wouldn’t be my flower if it didn’t have this at its centre.

My most cherished petal is my sexuality and gender identity. I am the first (very proud) gender-fluid bisexual in my family. The journey of coming out and discovering myself as a queer person while growing up in a society and family steeped in homophobia was, frankly, fucking tough.

The freedom and joy I feel at being able to express myself is hard to capture in words. The first time someone validated my identity as a non-binary person felt like an out-of-body experience, except that I was more comfortable in my body than ever before.

Another petal that makes me who I am is the fact that I am the oldest of six kids. From the earliest age I have been a caregiver, a protector, an educator and someone striving to be a good influence – but I am by no means perfect and I know that at times I’ve been both the hero and the villain in my siblings’ lives.

I am also the oldest of too many cousins to count. As someone who has had to look after and nurture almost every one of them, I’ve always felt it was my duty to make our family a safe place for them to be able to live life on their terms and express themselves openly, safely and with pride.

Looking at some of my younger cousins, I don’t think I’ll be the only openly queer family member for long. It’s a big weight to carry the responsibility of opening my family’s minds. They had been bolted shut to the idea that being gay, or trans, or a ‘feminine’ guy, or a ‘masculine’ girl isn’t just wrong or a phase, but is someone’s truth – someone stepping out of a hollow shell. That it’s someone choosing not to live and die miserably.

Another petal that makes me who I am is the unique way that I view this world. This is something that would never have been possible without the influence of my mum. I didn’t get to live with my mum much while growing up, but she’s in my life now and that’s what matters.

My mum is loving, generous, open-minded and so damn charismatic. Mum is understanding and fights for her beliefs and the beliefs of those she loves, even if she doesn’t always understand them.

It was my mum who first taught me that expressing myself emotionally, mentally, physically and spiritually was a radical act, and something to be proud of.

It was my mum who taught me that being gay wasn’t a sin, or something shameful; that it was something to celebrate. It was me living my truth. My mum taught me that while the world is full of both good and bad, expressing myself and living life on my terms is definitely part of the good.

Another petal that has shaped how my life has played out is the fact that I am the child of a criminalised man. I grew up bouncing between him and my nan.

It pains me to remember him during my childhood as a sad, scary, shallow and money-hungry man. I also remember him being outrageously funny and an amazing woodworker.

When my dad sings, he always finds a way to work himself into the lyrics like he’s Ice Cube or something. He is fiercely loving in many ways, and fiercely violent and harmful in others.

Dad has always struggled with his mental health and addiction, and has often relied on things like drug dealing to support us as a family. When he was a kid, society forced him to learn how to provide for himself in a world that didn’t want to see him survive – a world that told him time and time again that he was the problem.

It breaks my heart that my siblings and I also had to grow up in a world that told us time and time again that we were the problem. Despite my dad’s best efforts, he couldn’t protect us from this messaging.

I hate that my dad grew up in a world that saw him as a criminal from a young age, and I hate that the world sees me and my siblings as criminals because we’re Black and we were born to someone society has painted as a villain.

My great-grandmother and my great-great-grandmother were both part of the original Stolen Generations, and I know this is where my family’s pain started. I loved my great-grandmother deeply and remember her wisdom. I also remember the hurt she carried.

I don’t think any kid my age should understand the term ‘generational trauma’ the way I do. My dad has spent a lot of time in and out of prison and our relationship is complex. This relationship is not simply good, nor simply bad – it’s both and everything in between.

To my dad, I think I am many complicated things. I am his child, but I’m also the one who has had to step up many times. I’m the one who looks after him and who cares for him and his children, and sometimes I think he feels like I threaten his authority and his validity as a ‘man’ (whatever that means).

As I write this, my dad has been in prison for two years. For about a year and a half of this, he was awaiting sentencing. He’s due to come home any day now and to be honest, I feel so many complicated emotions about it. I feel excited. I feel scared. I feel heavy.

In so many ways my life is simpler without him around, and in other ways I feel his absence like a wound. Most of my childhood memories are traumatic. Some of the most vivid of these aren’t of trauma inflicted by my family, as the world so often wants to focus on, but rather trauma inflicted by the State.

I have countless childhood memories of police beating down my door to arrest my family members: while in the loungeroom watching Nickelodeon with my younger brothers asleep in my arms; while dozing off to sleep on a Sunday night; while at a wake for one of our family’s Elders.

The threat that my caregivers could be violently stolen from my life at any given moment always loomed large.

I remember this one time police forced their way in when I was about nine or 10 years old. I knew the drill by then and bundled up all my younger siblings and cousins into one room and hid under the quilt cover.

On this particular occasion, I heard the bedroom door open and felt the quilt being ripped from us. I opened my eyes to see a bright light shining in my face. It wasn’t until another officer entered the room and turned on the light that I realised that it wasn’t simply a torch, but the barrel of a gun pointing in my face. I was a child – no more than 10 years old.

This is the same night my dad got charged for resisting arrest and assaulting a police officer as he struggled free of their grip to come to me, his child who was surrounded by police.

This is the same night that I felt my heart rip in two as I saw my five-year-old brother, pinned to the window, screaming “Dad, Dad, Dad!” as he watched my father’s face being dragged along the concrete by four officers.

My heart broke with the realisation that my baby brother was going to grow up in the same world that I was growing up in. I need you to trust me when I say that violence by police officers towards Aboriginal people is real and I need you to trust me when I say that if you are an Aboriginal child whose parents have been criminalised, police officers see you as a criminal, too.

This message was drilled into my 11-year-old brain on another occasion when cops burst into my dad’s house, chaos ensued and my aunty ended up being held down by five police officers. I remember feeling rage boiling in my belly and eventually spitting from my mouth when, for the first time in my life, I told the police what I thought of them.

“Oi, you fucking pig. My aunty doesn’t fucking deserve this. My family doesn’t deserve this. What you are doing is fucking wrong,” 11-year-old me yelled.

Cool as a cucumber, through pursed lips, I remember this slimy cop’s reply:

“It doesn’t matter,” he said. “That’s gonna be you one day.”

Can you imagine hearing that as an 11-year-old?

Another petal that makes me who I am is my ability to survive. Just like my dad, my nan, my great-grandmother and my great-great-grandmother, I’ve had to learn how to provide for myself in a world that doesn’t want to see me thrive.

This means that I’m wickedly creative and it also means I can live off just oats, Weet-Bix and hot water for weeks on end. I’ve stolen more times than I can remember – sometimes to feed myself and my younger siblings, sometimes to keep up with the latest trend and sometimes because, if you were in my position, wouldn’t you, too?

You need to know, though, that this still doesn’t mean that I’m the problem.

Despite all of this – despite everything I have lived through, everything I have had to do to survive – I am still here. I am smart. I am funny. I am intensely loving and protective of my younger siblings, but man – I can be heartbreakingly cruel towards myself. I have a best friend who I love with the fire of a thousand suns. This best friend is teaching me how to accept love and care from others.

At 17 years of age, I started living alone in a high-density public housing block and there’s not a week that goes by that I don’t open my door to someone in need.

I am trying hard to finish school, but it’s not easy to write an essay on ‘Where I see myself in 10 years time and how school is going to help me get there’ when I don’t know where the money for rent or dinner is coming from.

It’s even harder when you get suspended for two weeks for smoking a cigarette. I can’t help but think that if Mr Vice Principal was also living in unsafe public housing and had their 56-year-old alcoholic neighbour banging on their door and hurling abuse all night, he too might want a cigarette on his lunch break.

Despite all of this, I am still here, sharing my story with you. Despite all of this, at 18 years of age, I can now call myself a writer.

I had always dreamed of telling complex stories, like the one that I have lived and am living, but from a vantage point miles away from that of the average white, middle-class reporter or researcher – and here I am, doing just that.

Here I am, sharing the stories that other people won’t let us tell, sharing the stories that help people understand that we are not the problem, sharing the stories that help other kids like me know that they aren’t the problem either.

Because I am not the problem.

We are not the problem.

This article first appeared in Archer Magazine #18, the INCARCERATION issue.