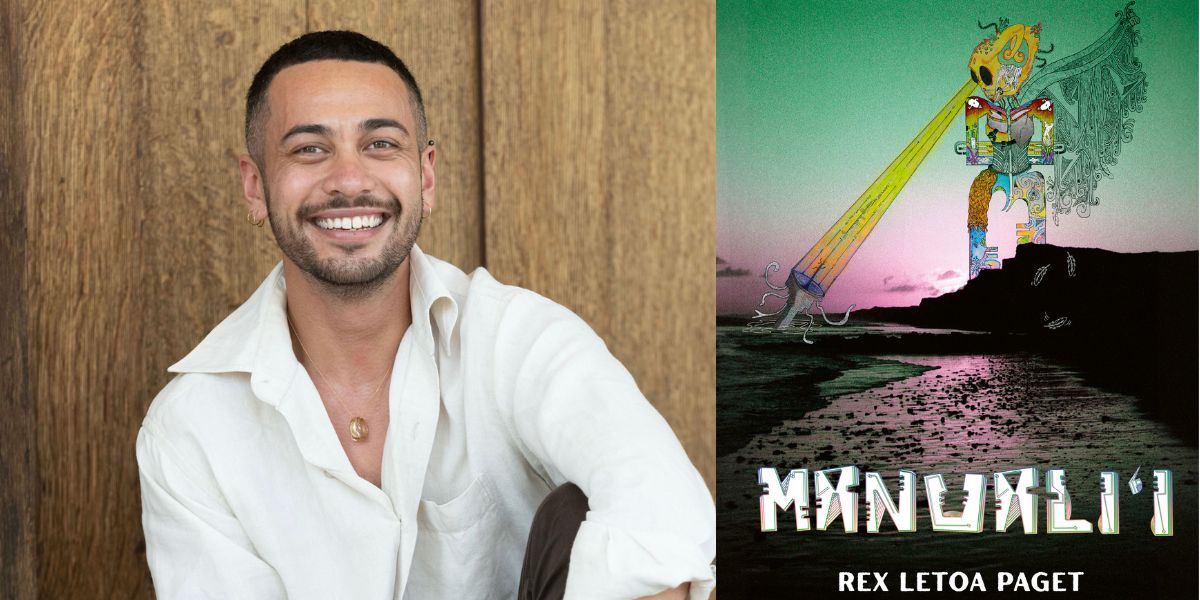

Archer Asks: Rex Letoa Paget on fa’afatama identity and healing through poetry

By: Dani Leever

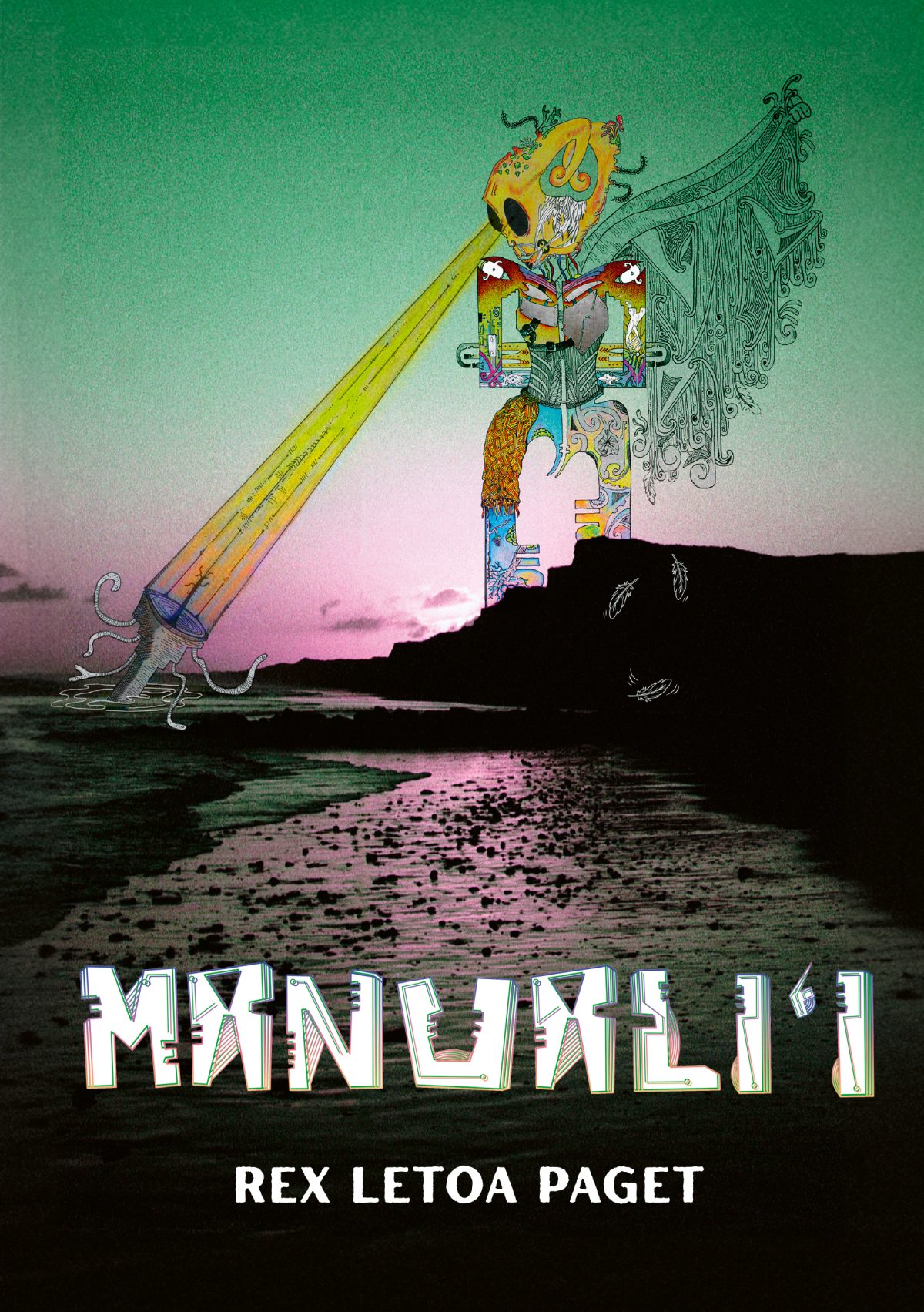

Rex Letoa Paget (Samoan/Danish) is a fa’afatama crafter of words born in Aotearoa, now living on the unceded lands of the Wurundjeri people. His poetry and storytelling are his compass through space and time. His works are giftings from his ancestors and have been published in Tupuranga, Te Tangi A Te Ruru, AUNTIES, Overcom, No Other Place to Stand: An Anthology of Climate Change Poetry from Aotearoa New Zealand, Rapture: An Anthology of Performance Poetry from Aotearoa New Zealand, Spoiled Fruit: Queer Poetry from Aotearoa, and Australian Poetry Anthology 10. His offerings are lessons, learnings, and acknowledgments for the timelines and traditions of yesterday, today and tomorrow.

Cover artwork and illustrations: Teina Tutaki

Author photo: Karen Wilson Photography

Dani Leever: Hi Rex, thank you so much for chatting with us! We’ve just finished reading Manuali’i ; it’s truly a moving collection with so much wit and heart! Can you share the process behind writing your debut collection, and what inspired the title?

Rex Letoa Paget: Hi Dani, thank you so much for having me and showing love to Manuali’i ! I’m really grateful.

I feel like the writing process was a lot of gathering by means of connecting into what I already had, so sharing stories and being present with my friends, family and loved ones. The process involved being curious about the “why” in all the things I was moving through at the time of writing – being a real Virgo about my feelings, basically.

I received so much wisdom and love from people around me, and I sort of took what they had so generously given and built on it. I found the title while I was talking to my mum about our family. She was telling me the real names of my Aunties and Uncles, before they immigrated to New Zealand and started to go by easier-to-pronounce names for white New Zealand.

One of my Uncle’s names is Manuali’i, meaning “bird of the Gods”, or “chiefly bird”. I just thought it was such a beautiful name, and I felt it really captured the vibe of the book as a whole, or what I was trying to tap into.

DL: You’ve mentioned that Manuali’i feels like a “homecoming”, which is a beautiful way of describing it. Can you elaborate why it feels this way?

RLP: I feel like I really opened up to the unknown while writing Manuali’i. I kind of let go of the perfectionist in me and just allowed myself to write, to flow, and to dream. I shared things on the page I hadn’t before, which in turn meant sharing them out loud with myself and sort of making them real.

I feel like Manuali’i is a homecoming because it really feels like my love and spirit on the page – something I never knew was missing in other works before, or something that took a long time for me to discover the language of. It’s like this journey of becoming after a period of loss, and it felt like I found myself and my voice again the more I wrote.

Image: Teina Tutaki

DL: Poetry can be a really powerful tool to explore and express identity; can you let us know how your craft has interwoven with your experiences as a fa’afatama?

RLP: Writing as a craft has been my lighthouse throughout life.

When I was a teenager, I’d write ‘songs’, but they never left the page, so looking back now I can see they were all poems. In those formative years, having a space that was just for me was hugely important – like my own world where I could create and write characters, or explore masculinity in a way I didn’t feel I was allowed to.

I felt a sense of safety within the pages I was writing, especially at a time where binary gender was so apparent and present. Poetry has always served as a wayfinding tool for me throughout so many eras. It feels natural now to be writing poetry about becoming someone I’ve always dreamed of being, but never quite thought was possible.

Writing those possibilities on paper from a place of love, community, family, friendship – and being alive and this all being real – sometimes it feels like a lil’ love note to my teenage self. Like, you made it, kid.

DL: Queerness and self-love are really strong themes throughout the book. How have you utilised poetry over the years to explore these topics?

RLP: Being queer is such a gift, and being queer absolutely saved my life. I’m so lucky to have found an amazing queer family in my early twenties that have kept me loving who I am and who always have space for me at their table, even with the new additions of their growing families. So when I write about queerness and how I am able to love myself, it feels like a shout out to them: an expression of gratitude, or an acknowledgment of appreciation for the love that we are pouring into one another.

I often reflect on how easy it feels for queers to show community care because it’s what we’ve had to build for ourselves from a young age. I remember the first queer sharehouse I lived in during my very early twenties, and how many different people we had crashing on our couch throughout the year, because they were in town for artist talks or panels, or just needed a safe place to be.

I remember the amazing conversations that would happen on the patio well into the early hours of the morning: about how we build a better world for the younger generation, what we could do differently, what was missing for us growing up. There was a lot of sharing of our own stories.

I remember after top surgery, my housemate – an older queer person – would make me dinner every night. I remember my former partner, after a year or so of us being broken up, coming over to help me shower.

These are acts of love, big and small, and I don’t know if I would’ve truly experienced love like that had I not been queer. It makes it so much easier to come back to yourself, and to live, laugh, love who you are.

DL: What role do you think poetry can play in expressing marginalised voices, especially in the context of the Pasifika and queer communities?

RLP: I think a lot of people who are put in the margins are naturals at storytelling. I guess we have to be, in a way, otherwise who else would tell our history or our truths in a way that honours where we come from?

I think poetry is another form of being able to go beyond the margin – to take up the whole page. I remember I did a 12-week paper in Wellington through Victoria Uni’s International Institute of Modern Letters, taught by Victor Rodger. It was a creative writing paper from Maori and Pasifika narratives, and it was hugely impactful on my writing.

I was lucky enough to have my portfolio marked by Tusiata Avia, and she gave me the advice to take up more space on the page – to write myself into the story more. “Tell me about how you experience the world and why.”

Through sharing that part of ourselves – however much you want to share – we open to the richness of who we are, what we are made up of, and how that honours our Elders and those who have helped set the path on fire.

DL: ‘Zapelu Kidz’ and ‘Ballad of my Bloody Brain’ demonstrate a really creative approach to formatting and use of white space on the page. How do you approach format when creating your poems?

RLP: I want to say just the vibe of the poem [laughs]. I feel like when I’m writing a poem, it tells me what to do. Some naturally just feel like they need the space of the page, others need the flow of a left and right margin, or to look and feel like an ocean or a river. Some feel like dancers and some are paragraphs.

I guess I go with how it feels at the time I’m writing – with the rhythm and the flow of the words. Other times, I’ll write in a certain format at first, put it down for a few weeks and when I come back to it, the whole format needs to change to be more loose or tight. I think when creating anything, listening to what you’re creating is a huge vibe for movement.

‘Zapelu Kidz’, Manuali’i by Rex Letoa Paget

DL: The ‘Elysian Plains’ chapter takes the reader on a profound journey through connection, heartbreak and grief. How do you feel that poetry can serve as a tool for healing and understanding in the face of grief and loss?

RLP: Poetry is the only way I know how to go through. When I was writing ‘Elysian Plains’, I was looking after my dad who had been diagnosed with terminal cancer.

My dad and I had our ups and downs through the years, as most families do, but it was so important for me to be able to show up for him. I think it was easy to write from a place of love and understanding in the face of grief and loss because I was healing this relationship alongside writing this chapter.

We were sharing with each other parts of our lives we had missed in the in-between. We were both leaning into each other, and I think we both surprised one another with where we had been. The poems just came naturally from that – from empathy and from listening.

Having time to say goodbye also made losing someone I love a lot easier to move through. We take time for granted a lot, but I reckon it’s the most valuable thing we have.

DL: Thank you so much for chatting to me, Rex! So what’s next for you?

RLP: Oooh, good question. I feel like I have just started to gather again since first starting Manuali’i. I’ve been enjoying this rest after releasing it. But now I feel I’m ready to start writing again, which means going out and gathering, actually looking at opportunities that come up and saying yes.

So we’ll see what 2025 will bring, but it’s already feeling more inspired!

Order Manuali’i by Rex Letoa Paget on the Saufo`i Press website.