Lesbian painting: Storytelling and reclamation through art

By: Stacey Bennett

By the time my kids are asleep and the dishwasher starts its hum, I’m only just beginning my night.

My studio smells of oil pastels and pencil sharpenings. Sixteen sketches sit in a loose pile on my desk – faces of lesbians I’ve met over the past few months. Each sketch carries a story that’s about to spill out of me. On the easel, another face waits. I dip a brush into ink, trace the line of her jaw, and the quiet of the house folds around me.

From the next room, my wife turns a page in her book. Our kids breathe heavily in their sleep.

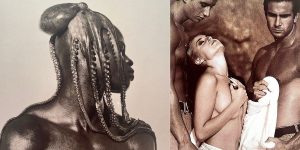

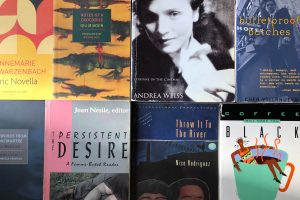

All paintings: By the author, Stacey Bennett

It’s a life I couldn’t have imagined when I came out at 14. Back then, I was brave, bold and utterly alone in the depths of narrow-minded suburbia.

I walked the halls of my high school as teens coughed lesbian into their hands. I feared they were right. I couldn’t bear the thought of kissing boys, but I didn’t yet know what being a lesbian truly meant.

The only other queer person I knew was a girl I’d met on an Avril Lavigne fan forum: a bisexual from America, 14,000 kilometres away. That was the closest thing I had to community.

My parents didn’t know what to do with me either. They’d mention the “unhappy” women who came into their automotive shop sporting short hair and scowls, with faces weathered by hard lives. It wasn’t said cruelly; it came from fear. Fear that my life would be harder, that I’d lose out on the hetero heaven they’d known.

I kept showing up anyway – with rainbow bracelets stacked on my wrist, my Discman switching between Avril and t.A.T.u., walking through clouds of Lynx Africa.

I didn’t know who I was becoming, only that hiding wasn’t an option. Decades later, I’m now creating the very thing I was searching for back then.

Image: Elyssa, Queer, born 1996. Mixed Media, 70x50cm, 2025.

Image: Flick, Lesbian, born 1988. Mixed Media, 70x50cm, 2025.

Even before I began painting, I knew the word “lesbian” carried baggage.

In the 1960s, television codes made it so that if a lesbian appeared on screen, they would receive ‘punishment’ for their queerness – often meeting a tragic end – as a warning against this ‘lifestyle’. The policy made it clear: lesbians were supposedly unfit for love, for happiness, for life itself.

By the 1980s, this punishment shifted in form, with lesbians recast as angry, hardened figures rather than fully realised people. Queer lives continue to be further distorted and reframed as fantasy, shaped through the patriarchy, and stripped their emotions and complexity.

Lesbians of Australia, my painting and storytelling project, began as my way of reclaiming the word “lesbian”. I was determined to take it back from algorithms and outdated codes, and paint it into something real, human and whole. To show that we’re complex, joyful, heartbroken, messy, alive.

Working on this series, most nights are filled with fast, loose brushes dragging across paper. The ink bleeds, drips, moves how it wants to.

Once the first layer dries, I return with another colour, layering ink to match the story the face carries. Then I go back again with oil pastels, which are messy and bright.

The colours sit on the surface of the canvas, like an emotion that won’t stay buried. I add the pastel in haste, trying to pin down the feeling before it escapes.

Image: Jane, Non-Binary Lesbian, born 1960. Mixed Media, 70x50cm, 2025.

Image: Annabel, Lesbian, born 1980. Mixed Media, 70×50 cm, 2025.

Each portrait begins with a conversation.

My subject and I talk about whatever they choose to share: love and loss, coming out, the journey toward self-acceptance and understanding. My studio holds the weight of their stories.

Some nights when painting, I feel the pressure to capture their stories perfectly. Other nights, I move quickly – not overthinking, letting the process lead.

The lines aren’t always perfect, but I’ve learned to accept that. Imperfection is part of the story. These portraits are more about a feeling than about photographic truth.

When I step back from a finished piece, I leave it on the easel in the heart of our home. For a day or so, my wife, my kids and I pass by the piece as we move through the house. After that, I know the artwork is complete.

Ellen* from Noosa sat for me last week.

She is a 40-something lesbian with a smile giddy with new love. She’d spent 13 years in a toxic relationship. Her first year alone, she told me, her motto was Just breathe. The next, it became Don’t say no – give it a go.

She radiated warmth as she recounted a spontaneous lunch with a truck driver and his dog. She told stories of joining Japanese drumming classes, of learning to DJ, of pole dancing and clubbing. When I painted her, I kept the colours warm, leaving space for her spirit to move.

Image: Ellen*, Lesbian, born 1977. Mixed Media, 70×50 cm, 2026.

Image: Ricki, Queer, born 1961. Mixed Media, 70×50 cm, 2025.

There was Deb, a lesbian in Sydney who grew up in an extreme Jehovah’s Witness cult. Her story stayed with me for days.

When she couldn’t deny her feelings toward women, she was exiled and cut off from everyone she knew, including her mother. But eventually her mum, unable to accept the cruelty of the rules she’d lived by, broke them: she stayed in contact with her daughter until the end of her life.

Deb said their bond was unlike anything else – a love between a mother and daughter that defied control and risked harsh consequences.

“Mum understood me,” Deb told me. “She never stopped.”

I cried after I met with Deb. I was moved by the strength and tenderness of their love. When I painted her, I used a muddy teal that felt both calm and heavy with emotion.

Image: Deb, No label, born 1966. Mixed Media, 70x50cm, 2026.

Then there was Cecily. When she spoke, her pace was slow and considered. Her words were filled with the wisdom of someone who lived enough life to see it whole.

At 83 years old, she carries the grief of losing her partner Margaret, who died in 2025 after a long battle with Alzheimer’s.

Cecily spoke of their life together: the laughter, the rhythm of companionship, and the care that filled their final years. She didn’t avoid the difficult parts. She told me about the ‘lion’ within Margaret, who fought fiercely to stay with her as long as she could, and the one within herself that gave her the courage to love and to keep showing up through the decline.

When I painted them, I placed their portraits side by side to dry. Together once more.

Image: Cecily, Lesbian, born 1942 . Mixed Media, 70x50cm, 2025.

Image: Margaret, Lesbian, 1929 – 2025. Mixed Media, 70x50cm, 2026.

T hese stories help this project feel far bigger than I’d ever imagined.

I thought I was painting portraits of lesbians. Instead, I’m capturing what it means to feel loneliness, courage, connection and love, all tangled together with queer complexity.

My moments painting vary from slow and steady to chaotic. My kids run through the studio with Pokémon cards, trucks and eager hands ready to join in. I love having my family as part of the process. My wife will ask the story of the woman on the easel. My son likes to play Spot the Difference between the photo and the painting.

Sometimes I miss bedtime. Sometimes they go to the park without me. But they know why, and they understand what this project means to me.

It’s no longer a hobby; this project consistently hums inside me.

Image: Anna, Lesbian, born 1978. Mixed Media, 70×50 cm, 2025.

Tonight, the house is quiet again.

The dishwasher hums. My wife closes her book and joins me in the studio for a moment, makes an approving comment about the woman on the easel, then goes to check on the children.

I rinse my brushes and turn off the lights. The studio glows faintly with colour. Soon there will be portraits of over a hundred lesbians, holding each other in the dark, ready to be seen.

*Name changed to protect the anonymity of the portrait sitter, as requested by the participant.